by Dr Donald Lawson, Ufac (UK) Ltd, Newmarket, Suffolk

Poor fertility represents one of the largest losses to the UK dairy herd. These are incurred from cows being culled, loss of potential milk yield and reduced number of calves being born. Poor fertility also complicates the management of the dairy herd and often means that milk produced at the wrong time of year receives a price penalty from the milk purchaser.

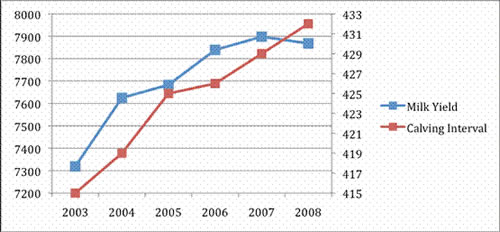

Latest figures from the Cattle Information Service (CIS) from over 315,000 lactations from England, Scotland and Wales show that fertility, as measured by calving interval, continues to decline at an alarming rate.

Calving interval has increased from under 400 days a decade ago to 430 days for the year ending September 2008. The average time to conception is now 150 days which means cows are in milk for almost five months before getting back in calf.

Alarmingly, while the trend has previously been for milk yield to increase along with calving interval, over the last three years the milk yield increase has stalled while calving interval has continued to increase. Fig1 shows the data from the last five years.

The increase in calving interval over time is due to a large number of factors including genetics, management and nutrition. Of concern, however, is that calving interval probably under-estimates the problem of poor fertility, as cows culled for infertility are not included in the figures. Bristol University vet, Chris Hudson, has updated the financial losses from these longer calving intervals and puts the loss at £5.60 per extra day for a calving interval range of 426 to 455 days. The benefit of reducing calving interval by just 30 days is therefore £168 per cow.

To put this figure in perspective it is roughly equivalent to increasing yields by 1,000 litres per lactation, assuming a margin over purchased feed of 17p per litre. Which would be easier to achieve – increasing yield or improving fertility?

How can nutrition help reduce the problem of poor fertility and potentially improve financial returns of the dairy herd?

The key factor in the relationship between nutrition and fertility is energy supply. Energy supply is a factor of the energy density of the diet and the dry matter intake. The adequacy of the energy supply to the dairy cow can be measured by blood levels of Non-Esterified Fatty Acids (NEFA), Beta Hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and glucose. It can also be measured more practically on the farm by the change in body condition of the cow. If energy supply is inadequate body fat will be mobilised to try to meet the shortfall and body condition will be lost. A scoring system of 1 to 5 is generally used to measure body condition where 1 is too thin and 5 is excessively fat.

The effect of poor energy balance on fertility starts with the dry cow in the 3-4 weeks before calving or what is also known as the transition period. Poor nutrition during this period will result in a longer period before ovarian activity resumes, poorer heat signs and lower conception rates to first service.

A large study in Israel showed that cows losing condition – ie being short of energy during the transition period – showed greater levels of anoestrus, increased metritis and were more likely to still be not pregnant 150 days into lactation.

A trial at Edinburgh University in Scotland showed conception rates to first service for cows fed silage and straw during the transition period were 29 per cent compared with 50 per cent for a group fed silage and concentrates.

Poor energy balance during the transition period, therefore, has a major effect on fertility. Consequently, the plan should be to feed the best of everything in the last month before calving. Dry matter intake should be maximised. Transition cows should receive the same forage as milkers along with concentrates and a specific transition-cow mineral.

Milk fever, retained placenta, ketosis and displaced abomasum are all health problems related to the transition period. These will reduce dry matter intake after calving and should, therefore, be minimised by the management and nutrition of the transition cow.

The link between negative energy balance and poor fertility is clearer still in early lactation. The freshly-calved cow often struggles to consume enough energy to meet the demands for milk production so body fat is mobilised to try and reduce the deficit.

This mobilisation of fat can again be measured by the loss of body condition. The greater the loss of body condition the lower the fertility as shown in below.

Days to 1st ovulation

Less than 0.5 - 27

Between 0.5-1.0 - 31

Greater than 1.0 - 42

1st service conception rate (%)

Less than 0.5 - 65

Between 0.5-1.0 - 53

Greater than 1.0 - 17

Butler & Smith 1989 J Dairy Science.

For a cow, one point in body condition score equates to 30kg bodyweight and for a heifer, 15kg.

A typical freshly-calved cow yielding 40kg of milk requires 295 MJ of energy at a time when dry matter intakes (DMI) have not yet reached optimum. Even assuming a very-generous DMI of 24kg, the energy density of the diet, which must be consumed to avoid weight loss, is 12.3MJ/Kg DM.

Typical diets of high-quality forages and straights will be closer to 11.8MJ/Kg DM giving a deficit of 12MJ - equivalent to a 0.5kg daily bodyweight loss. Drop intakes by 1kg DM and the deficit becomes 24MJ and the bodyweight loss is 1.0kg per day with a devastating impact on fertility.

Avoiding the loss of body condition requires the diet to maximise the dry matter intake and energy density to meet the cow’s energy requirements.

To achieve optimum dry matter intake it is important to ensure that the diet is palatable, adequate feeding space is provided, the diet is pushed up frequently and that there should be some feed left and this should be cleared away daily. A plentiful supply of clean water should always available.

Energy density can be boosted by the addition of high energy density fats to the diet. Especially useful are those types which do not have a negative impact on dry matter intake. This can help bridge this energy gap and prevent negative energy balance. For the example used above, adding 0.6kg of fat will increase the energy density of the diet to 12.3MJ and will, therefore, meet the cow’s energy demands.

The relationship between bodyweight loss and fertility could not be clearer. Therefore, trying to reduce bodyweight loss must be a priority in any effort to improve fertility.

One critical area is the ration plan. It should not be accepted that 0.5kg bodyweight loss is inevitable. Assuming that this weight loss will happen make the feed cost per litre on that particular feed plan look cheaper. It could, perhaps, save as much as 25p per cow per day which would be £25 per cow over the first 100 days of lactation compared with a feed plan using a high energy density fat supplement to achieve zero liveweight loss.

However, when this saving is set against a loss of £5.60 a day for just one extra open day this saving is seen clearly to be false economy!