Sometimes hens feather peck and cannibalise. We have all seen it happen. Do we know why? Sometimes. It is not always clear why some flocks behave impeccably and some don't and for the ones that misbehave, we often don't know what the trigger was that set off the undesirable pattern of behaviour. The following are some of the most likely factors that could be associated with these vices:

Stressors.

Incorrect nutrition / low nutrient intake.

Poor liveweight / physiology of the pullets and therefore of the hens.

A genetic strain that has aggressive tendencies.

Poor layout and choice of equipment.

Parasites.

Incorrect light intensity, especially in the nests.

Poor litter quality.

Poor use of the range area.

In real life, on the free range farm, is it likely that all of the above factors can be optimised all of the time? No, even on a farm where the management was exceptionally good and the performance and low mortality of both the previous and subsequent flocks has been exceptional, disasters can occur. A producer in Norfolk kindly volunteered to allow this farm to be used for the following 'trial' to examine what would happen if the hens were not beak-trimmed.

In July 2003 the UK branch of the World's Poultry Science Association held the 27th Poultry Science Symposium on the WELFARE OF THE LAYING HEN. At that Symposium there were many interesting papers and poster presentations. One of the posters looked at: THE PERFORMANCE AND BEHAVIOUR OF NON BEAK-TRIMMED HENS ON A FARM PRODUCING ORGANIC EGG. The following outlines what happened.

On an organic farm in Norfolk, three houses of a similar size and construction contained 3,000 laying hens / house, each flock with a different commercial breed, all reared by the same firm but on different farms. None were beak-trimmed. The nutrition was the same in all houses. They were fed a range of commercially available organic feed, in crumb form, that has always given satisfactory results. The stocking density was 6 hens / m². Veterinarians and the RSPCA were informed of the progress of the flocks and liaised as necessary, both in the planning and management of the 'trial'.

Behaviour and performance of the hens differed markedly:

House 1 / Breed A

The flock was depopulated early (when 67 weeks old), for welfare reasons.

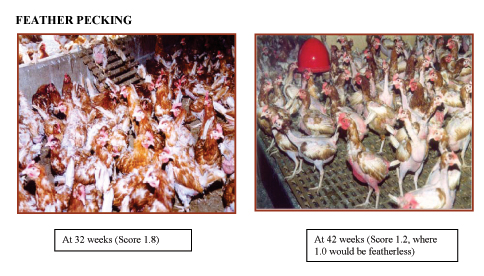

Feather pecking was extremely severe, leading quickly to 'bald' hens and then cannibalism. (See the photographs taken when 32 and 42 weeks).

Feed intake was very high (144 g/hen/day).

Hen Housed egg production was depressed (245 eggs to 67 weeks).

Mortality was very high (16.5%).

Egg quality was poor (pale shelled eggs) (12.7% seconds).

Financial margin over feed cost: 78% lower than HOUSE 3.

House 2 / Breed B

The flock was depopulated early (when 65 weeks old) for welfare reasons.

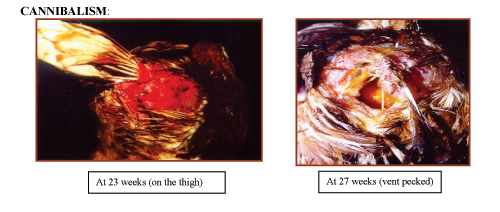

Well-feathered hens started cannibalising at an early age and then feather-pecked. (See the photographs when 23 and 27 weeks)

In an effort to stem cannibalism, they were beak-trimmed when 29 weeks old (with veterinary approval).

Unexpectedly, beak trimming when 29 weeks old had no adverse effects on their performance.

Thereafter cannibalism quickly resumed, leading to high mortality (14.2%).

Hen Housed egg production was depressed (240 eggs to 65 weeks).

Financial margin over feed cost: 61% lower than House 3.

House 3 / Breed C

Performance and welfare (feathering and cannibalism) were exemplary with no problems whatsoever.

Performance to 72 weeks:

Hen Housed egg production 306 eggs: Feed consumption 128 g/hen/day: Mortality 4.8%: Financial margin good.

CONCLUSIONS

This farm scale 'trial' showed that the performance and behaviour of non-beak-trimmed hens could be unpredictable. Beak trimming Breed B when 29 weeks old surprisingly appeared not to have been stressful. Where the hens' behaviour in Houses 1 and 2 was adversely affected, financial margins were markedly reduced. Feather pecked hens were unable to continue to lay eggs whilst trying to re-grow feathers. The hens showed only a short-term interest in 'toys'. Feather loss was due to both aggressive and submissive pecking. Mortality was predominantly due to cannibalism, vent pecking and to peritonitis. Once started these vices and the peritonitis became unstoppable.

DISCUSSION

On this farm and on this occasion, there were clear differences in behaviour (feather pecking and cannibalism). However, because of the multi-factorial aetiology of these vices, further investigations are warranted in trying to establish whether there are indeed differences in the behaviour of non beak-trimmed commercially available brown egg laying hybrids and what the aetiology of feather pecking and cannibalism in free range hens is.

This 'trial' was extremely interesting and of potential value to free range egg producers. It endorsed that things can go wrong, even on very well managed farms and that housing pullets that have not been beak-trimmed may well be risky. The following photographs taken during this 'trial' illustrate all too clearly, just how disastrous things can get:

CANNIBALISM:

FEATHER PECKING

Where feather pecking and cannibalism occur, what is the outcome?

A. For the hens there could be pain, stress and death.

B. For the producer there is emotional tension caused by the difficulty in trying to stem the unstoppable problem once it has started, coupled with the frustration of dealing on a day to day basis with a flock that are unsightly and stressed. In addition, the business is likely to be financially crippled because of:

a) Reduced egg sales, due to hens that are trying to re-grow their feathers being unable to lay at the same time. Also of course, dead hens don't lay eggs!

b) Increased seconds due to pale shelled eggs.

c) An increased labour input which usually proves to be fruitless.

So what can be done? Clearly it would be desirable if no beak trimming was carried out on pullets. Therefore intense effort is necessary to get all of the factors that are listed at the beginning of this article optimised on both the rearing and laying farms. By doing this the necessity for beak trimming could be decreased. Realistically however, further investigations are entirely necessary to try to establish whether free range producers can be brave enough to dispense with beak trimming.

Until this is done, the following seems to offer a compromise that could hopefully be acceptable to all parties. Since 2003 a system has been introduced that seems to be successful in reducing the stresses to the chicks (and the staff) of beak trimming. This Nova-Tec Infra Red Beak Treatment System results in the hens having less pointed beaks. The beaks are blunted rather than being pointed and perhaps shaped like the beak of a crow. The process is done at the hatchery before delivery of the chicks to the rearing farm and seems to be promising. Obviously no guarantee can be made that this beak treatment system will eliminate feather pecking and cannibalism. However it does not seem prudent to ignore something that may reduce the risks of these potentially disastrous traits.

In conclusion, pertinent questions on feather pecking and cannibalism are:

1. Is it possible to eliminate entirely feather pecking and cannibalism in free range flocks? No, not at the moment.

2. Is it sensible and desirable to try to reduce the risks? Yes, definitely.

3. Is it necessary to do further research on the aetiology of feather pecking and cannibalism in hens? Undoubtedly, yes.

4. Is it realistic to expect that at the moment and at all times, the multi-factorial triggers of cannibalism and feather pecking can be avoided on free range farms? Regrettably, no.

5. Does beak trimming reduce the risks? Yes.

6. Is it prudent to remove the option of using an apparen