Britain's free range hens set to join lockdown

As the country comes out of a national lockdown into Covid-19 tiers, Britain's free range hens look set to start their own lockdown.

While some may consider these issues bad enough, producers in 2016/17 also had to worry about whether they would lose income due to their eggs being downgraded from free range to barn as a result of an extended housing order.

As of 29 November, the UK or devolved governments have not applied a housing order this season as yet, and with the latest outbreaks in turkeys in Northallerton, a housing order looks imminent, according to the British Free Range Egg Producers Association (BFREPA).

The free range egg industry body reflects on the issues which faced producers in 2016/17 when Defra applied a housing order.

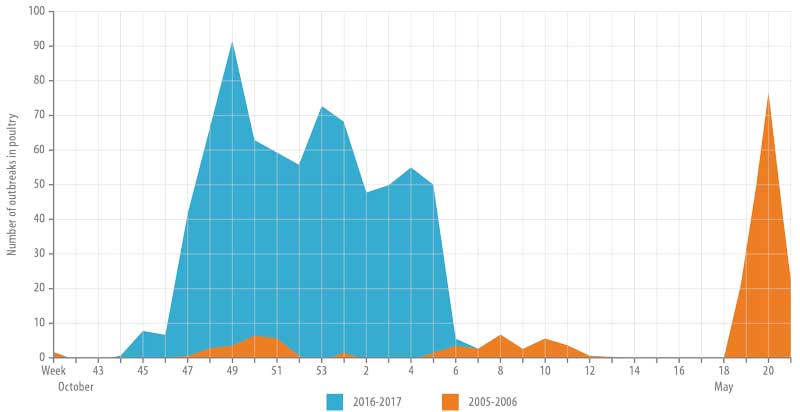

The last two major HPAI outbreaks were in 2005/6 and 2016/17. In 2005 the UK was facing H5N1, which was potentially far more serious for humans, but it did not involve any housing orders in the UK or the EU, although the Dutch did house.

Thus, because the virus behaves differently in H5N8, the 2016/17 epidemic provides a better experience for this upcoming season.

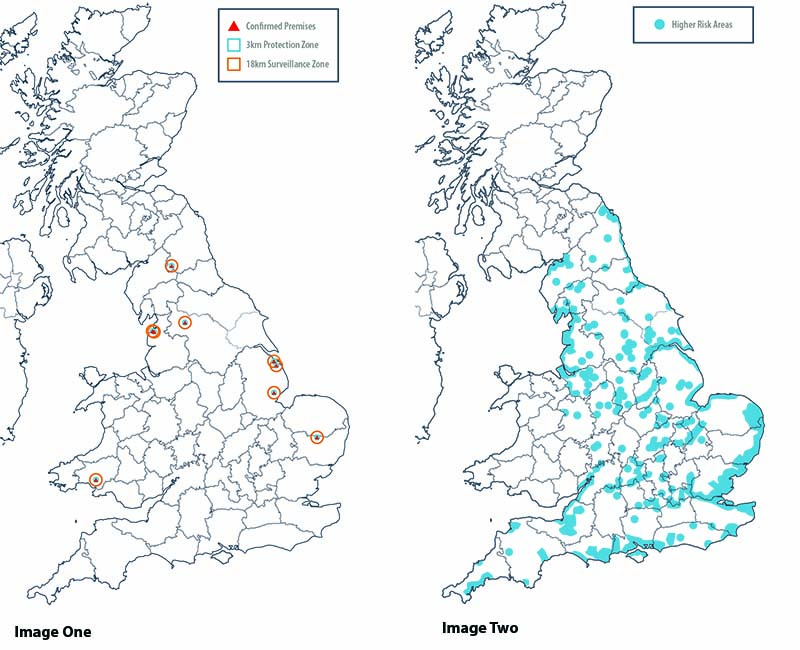

The 2016-2017 outbreak of H5N8 HPAI in the UK consisted of ten infected premises, distributed across six distinct geographical areas of England and Wales: Lincolnshire, Lancashire, Suffolk, Carmarthenshire, Yorkshire, and Northumberland.

Three of the outbreaks, in Carmarthenshire, Yorkshire and Northumberland were on single smallholder premises.

The three infected premises (IPs) in Lincolnshire were turkey units, and the three infected premises in Lancashire were game farms and were all associated with one business enterprise. The premises in Suffolk was a broiler breeder unit.

Apart from the game farms in Lancashire, all the outbreaks resulted independently from direct or indirect primary incursions from wild birds. The IPs in Lancashire involved a subsequent spread between related premises as a result of business activities.

The links to wild birds were consistent throughout 2016/17, and the same pattern is forming this autumn as winter nears.

Indeed, the worrying aspect of this winter's pandemic is that it has started much earlier than in 2016, making any decision on the timing of any housing order that much more important.

Back in 2016/17, Defra confirmed 38 different wild bird species as carriers across the EU. These were:

• Ducks (40%): Tufted (15% of all reports); Widgeon; Mallard; Teal; Pochard; Goldeneye; Eider; Shelduck

• Gulls: Black-headed; Herring; Great Black-backed; Common tern;

• Other Waterfowl: Geese (Greylag, Canada, Brent), Coot; Moorhen; Heron; Swans (Mute and Whooper); Cormorant;

• Waders: Green Sandpiper; Grebe; Curlew;

• Birds of Prey: White-tailed Eagle; Common Buzzard; Peregrine Falcon; Eagle Owl; Northern Hawk

• Corvids: Crows; Magpie; Hooded Crow; Raven;

• Captive birds: Swans; Goose; Pelican; Emu; White Stork, Harris Hawk

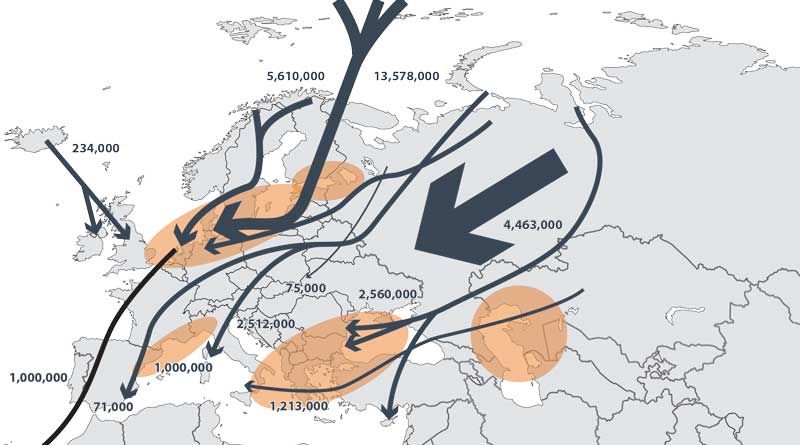

The most significant carriers were ducks, but gulls were increasingly suspected in the UK as the pandemic continued into February 2017. This autumn, wigeon ducks have been associated as the main carriers in the Dutch poultry outbreaks and in the first UK infected premises in Cheshire.

This site borders the Mersey and Dee estuaries, common wintering sites for wigeon, which have migrated down the continental European seaboard and across to the Mersey and other English estuaries.

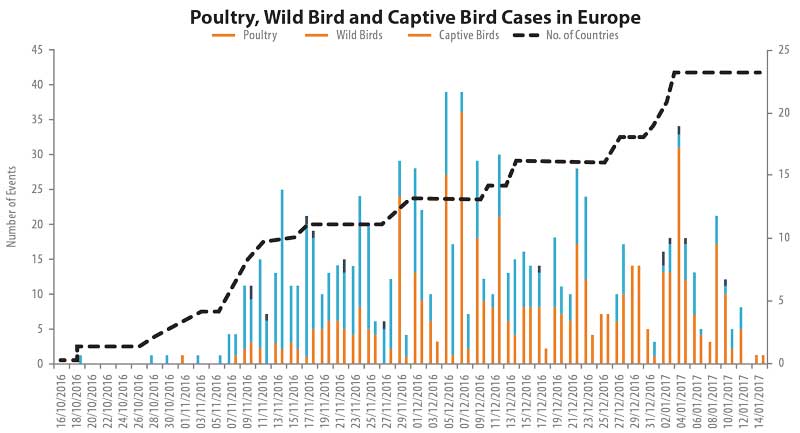

While the 2016/17 and 2020 outbreaks follow similar patterns in terms of virus strains and wild birds as carriers, the one difference is that this year the pattern has started earlier.

Cases in western Europe did not begin until the middle of November in 2016, but this year the first commercial poultry case was notified in the Netherlands in October, together with many wild bird cases.

While producers received early warning of the approach of H5N8 from a similar but more widespread pattern of infection in Russia in June, with many Russian poultry farms infected in July, it was a shock to find the first wild bird case in Holland in early October.

In 2016 the virus spread southward into Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italy rather than into western Europe, as has happened this year.

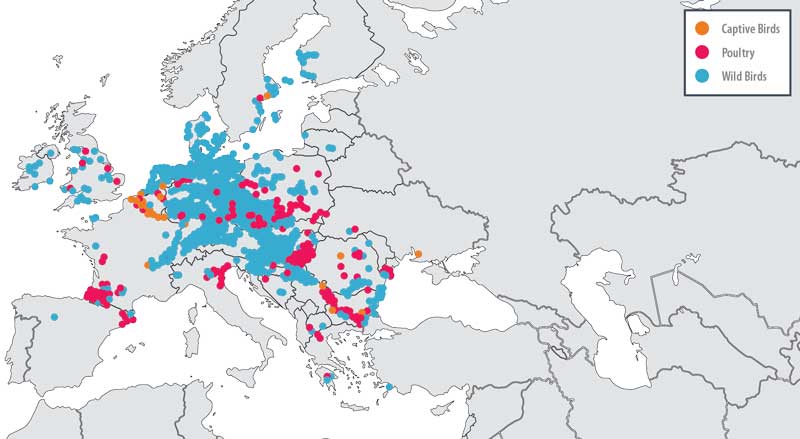

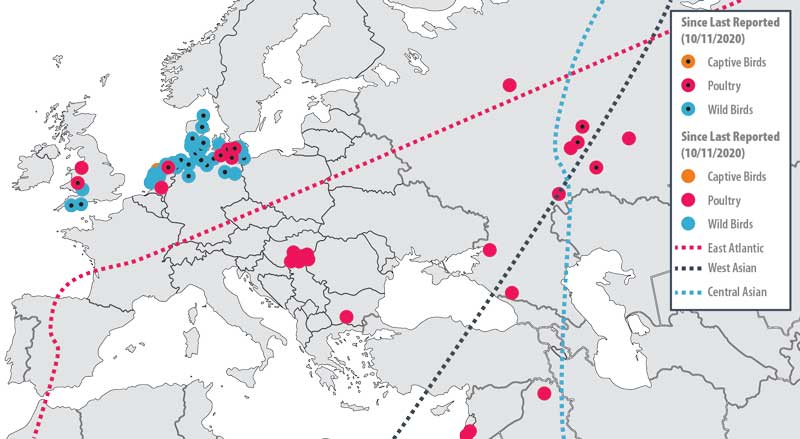

The map below shows the cases so far this year. It is striking how, apart from the poultry farms in southern Russia, the vast majority of central Europe has been unaffected so far compared to 2016/17 (map above). The infection has followed the East Atlantic wildfowl flyway direct to the UK.

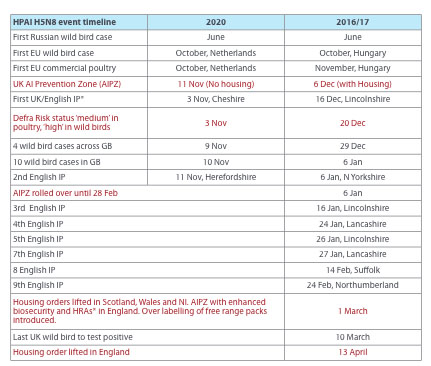

The timeline of events for the HPAI epidemics is summarised in the table below. It indicates that this year's epidemic is not only some 6-8 weeks ahead of events in 2016 but is also geographically more focused on western Europe and the UK than central Europe.

Indeed, this year's first EU and UK poultry IPs are approximately six weeks ahead of 2016, as is the number of wild bird cases. The second HPAI H5N8 IP's timing is nearer to 8 weeks ahead of what would have been expected.

Given the rapid onset of the virus and the probability that it would remain a risk to free range flocks until mid-April (as in 2017), the timing of the implementation of a housing order is vitally important.

Producers are only guaranteed to maintain a free range egg premium price for up to 16 weeks of housing. After that, the risk of free range eggs being downgraded to 'barn' is a real risk.

Table one below shows (in red) the policy decisions made by the UK's devolved administrations. In 2016 a housing order was imposed by the English, Scottish and Welsh governments on 11 November (N. Ireland imposed one a little later), before there was a single case of infection in the UK.

At the time, the industry supported such a move thinking that it would only be in place for 30 days, but it was rolled over time and again and was not lifted in England until 13 April.

However, the free range marketing status of eggs expired on 28 February 2017, and this led to a very difficult period of uncertainty for producers with a conflict between industry, retailers, and government.

The requirement for housing within Higher Risk Areas (HRAs) from the 28 February created tensions between producers on either side of a HRA boundary.

This was particularly evident between producers on the English side of the Severn. They had to risk losing their free range premium due to the housing order while those on the Welsh side of the Severn were unaffected.

Even within BFREPA, policy decisions were conflicted by those members outside HRAs, who did not see the problem, and those stuck within a HRA who risked having their eggs downgraded.

Throughout January and February 2017 different solutions to the free range marketing status problem were explored by BFREPA, and other industry representatives, to find a compromise that would allow housed free range flocks (in HRAs) to maintain their free range egg marketing status.

As the egg marketing rules derive from EU regulations (and this will continue – for the time being- even after Brexit), all parties hoped that the EU would solve the problem. The Dutch (supported by the Belgians) placed the issue on the AOB of an EU Agriculture Council meeting in January.

They did not apply – as hoped - for a derogation to the EU egg marketing regulation but asked for exceptional measures to be used to tackle market disruption in the Common Market Organisation. The UK government did not support this or any other EU member state proposal to resolve the problem. No EU solution emerged.

At the national level, the industry argued that the housing element is removed from the AIPZ and replaced with enhanced biosecurity measures that could make a valid reduction in the risk of disease transmission while allowing hens on to the range.

This line of work provided some hope but relied on a Defra risk assessment to show that these enhanced measures could be effective.

The third strand taken by some in the industry was to take legal advice/Council's opinion on how the EU's egg marketing regulations were being currently interpreted by Defra (with regard to the 12-week derogation) in the UK.

The final and ultimately most successful approach was via the supply chain. The challenge to retailers and packers of re-labelling and creating new packaging for shell egg and egg ingredients, assuming they had to be downgraded from FR to barn, led to a labelling solution brokered between British Egg Industry Council (BEIC) and the British Retail Consortium (BRC).

The proposed solution was an over-sticker, which would be stuck onto existing FR packaging. This would have to be applied manually in some cases if a packer did not have the automated machinery to do this.

While this did involve extra labour cost for some, it remained an eminently more practical solution than to produce barn packaging, which would lead to wastage, remove the free range premium and seriously damage the longer-term image of free range.

While the BEIC/BRC solution worked for Lion producers supplying packers, BFREPA produced labels for members who were self-marketeers or non-Lion producers. On the sticker, BFREPA mocked up some words to satisfy legal opinion on the labelling rules.

Lion scheme members labelled all free range packs with the agreed words as requested by retailers, regardless of whether eggs were being laid by flocks housed (in HRAs) or not housed (outside HRAs). As it was considered important to keep marking eggs on farm, and to avoid costly change to print heads, the number '1' was still printed on eggs.

The retailers (BRC) required that pack labels accompanied by shelf labelling, point of sale information, and a website for consumers to obtain further information to keep consumers fully informed and not misled.

While this solution resolved the crisis in 2017, there is no guarantee that the same approach would work in 2021. The government never challenged the over labels used and kept quiet throughout the crisis in 2017, although it could easily have picked holes in the label's compliance with the egg marketing regulations.

Having observed the supply chain solution in 2017, the government may not take such a relaxed approach this time.

If devolved governments had followed the 2016 experience and had applied a housing order as part of the Avian Influenza Prevention Zone on 11 November this year, producers would again have to worry about their free range egg marketing premium after 1 March next year.

In 2017 the Housing order (AIPZ) in England was lifted on 13 April. If this was repeated in 2021, the housing order would have to come into force on or after 22 December for flocks to maintain their free range marketing status throughout housing.