A risk assessment is recommended for at-risk farms as tick numbers are due to peak in the coming weeks, according to experts.

Ticks, which transmit infections such as bovine babesiosis, are expected to peak in some areas of Britain in the next few weeks, research shows.

Farmers in areas with a history of this disease, also known as redwater, are being encouraged to take extra precautions to protect susceptible stock during this period.

Ticks are found throughout the country, but reports from cattle farmers indicate clear regional patterns.

Recent research shows that farmer reports of ticks on cattle are highest in north Wales, northwest England and western Scotland.

Farmers in the south west of England reported the highest cases of redwater in cattle.

Dr Rose Vineer, veterinary parasitologist at the University of Liverpool, said: “6% of the cattle farms surveyed reported that their cattle had ticks, but in ‘hotspot’ clusters prevalence was higher, ranging from 48 to 100%.

“Two per cent of cattle farms surveyed reported tick-borne disease. However, out of these a third reported tick-borne disease in their herd.

“As expected, the study highlighted upland grazing as a significant risk factor for reporting ticks on the farm.”

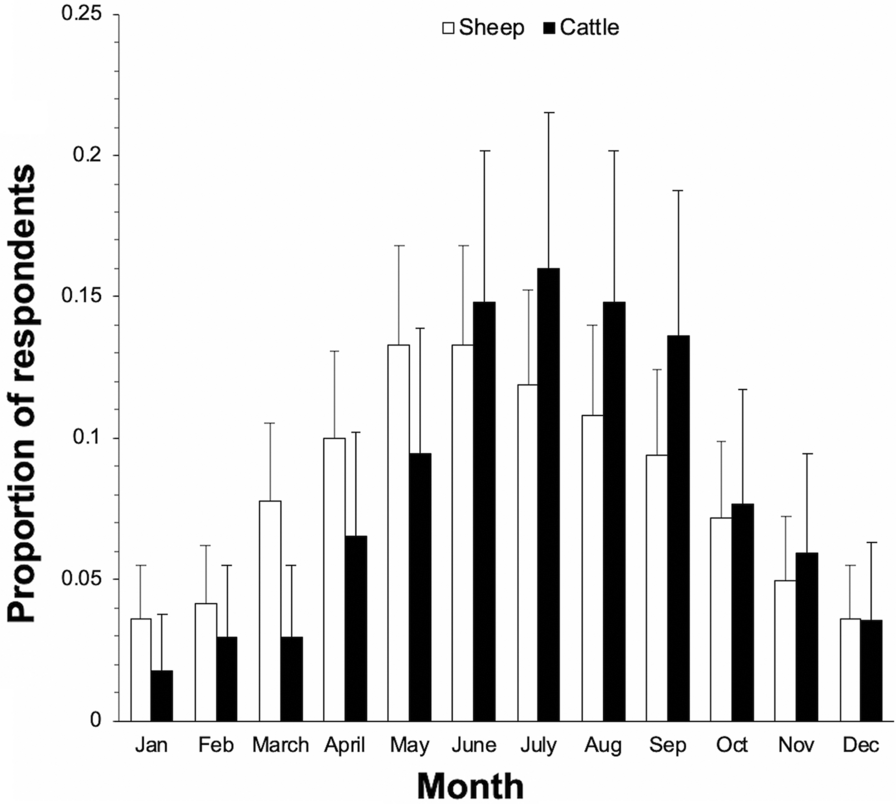

Ticks were reported in all months by farmers filling out the questionnaire – with the highest proportion of reports during May to July.

Engorged ticks are easily visible on infested cattle and typically found concentrated in the skin folds between the chest and front legs and in the groin around the udder or scrotum.

Ticks can vary in size depending on their stage of development and how much of a blood meal they have taken. Bites are often inflamed and swollen and may become infected and attract flies.

Signs of redwater fever may be the first indication of a problem, with acute disease occurring within two-weeks of an infected tick first feeding.

Animals are typically severely depressed showing high fever, respiratory distress, pipestem diarrhoea, as well as the dark stained urine, which gives the condition its name. The disease is often fatal unless diagnosed and treated promptly

Tick control is difficult because ticks spend most of their life cycle away from the host, sheltered at the base of thick, damp vegetation.

Attempts to reduce tick populations by environmental treatment with acaricides is unacceptable because of their effects on other invertebrates.

The Control of Worms Sustainably (COWS) group, which advises on ectoparasites as well as worms and liver fluke in cattle, suggests a reduction in the tick population can be achieved through pasture improvement, drainage and scrub clearance, although this is a long-term exercise requiring sustained effort.

Meanwhile, factors such as changing weather patterns, increased deer populations, which also act as tick hosts, and agri-environment schemes are expanding tick habitat.

A range of pour-on pyrethroids have UK licence claims for treatment of ticks on sheep, but no products in the UK have a label claim for cattle.

“Tick-borne disease of cattle can cause significant problems for farmers in ‘hot spot’ areas,” Dr Vineer explained.

“As with all parasites, it is worth farmers carrying out a risk assessment of their stock and the pastures to be grazed and then consider moving at-risk cattle onto safer pastures.”