Sheep farmers could profit post-Brexit if they allowed land to naturally regenerate into native woodland, according to new research.

Most sheep farms in the UK are unprofitable without subsidies, but farmers could make a profit if they use their land for tree planting, the study said.

It found that farmers would no longer need to rely on subsidies if they allowed native trees to return to their land and sold credits for the carbon dioxide (CO2) the forest absorbs.

The National Sheep Association (NSA) said the report ignored the fact that British sheep farming was 'more than a business' - as farmers gained 'huge pride and satisfaction from farming sheep'.

But the University of Sheffield study, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, calculated that most sheep farms made a loss without government subsidies, with only the most productive breaking even.

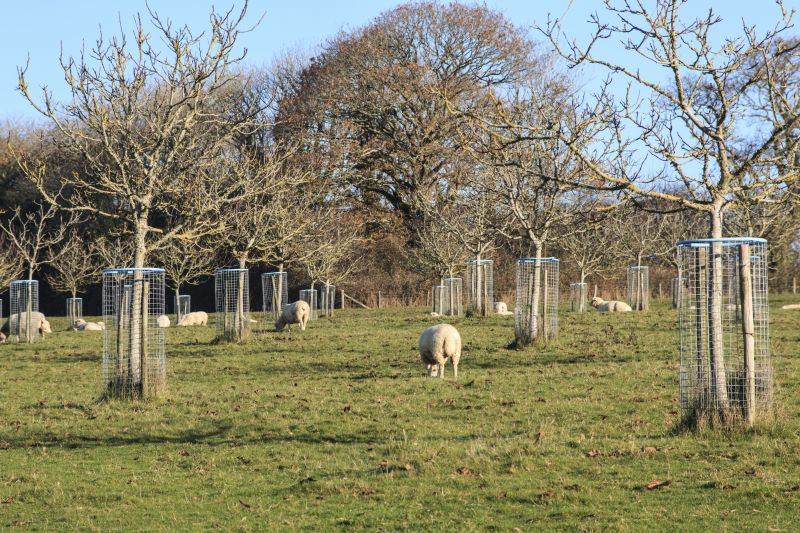

The authors found that farmers with at least 25 hectares of land could turn a profit if they allowed it to naturally regenerate into native woodland and were paid as little as £3 per tonne of CO2.

If farmers were paid £15 per tonne of CO2 by businesses and individuals looking to offset their emissions, forests of any size would make a profit.

It comes as the government is set to pay farmers for public goods through the new Environmental Land Management scheme post-Brexit.

Professor Colin Osborne, lead author of the study, said forests that sell carbon credits can be economically viable – so it made sense for the government to help farmers transition.

“Using public money to actively prevent reforestation in the UK and Europe is morally questionable given the pressure western governments place on the global south to end tropical deforestation," he said.

“Ultimately, these come down to political questions of how we want our countryside to be used, how we value livestock production over the global costs of climate breakdown, and how the government supports farmers and rural communities.”

According to the research, such a shift would also cut greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, support wildlife and help to prevent flooding.

It added that converting land to ‘carbon forests’ without the costs of planting trees was possible for farms close to existing woodland, which provide a natural source of seeds.

However, the research found that even farmers who would need to plant the trees could break even if they were paid as little as £42 per tonne of CO2.

The current market price of carbon is £15 – however, the government values the true cost of CO2 to society at £52 per tonne, suggesting tree planting could make economic and environmental sense if the carbon price increased.

In England, the government also covers 80 per cent of the cost of tree planting – a system that would allow farmers to turn a profit by charging just £9 per tonne of CO2

Responding to the report, Phil Stocker, chief executive of the National Sheep Association (NSA), said that expecting farmers to give up sheep and plant forests 'ignores two basic facts'.

“Sheep farming is more than just a business, it is part of our culture and heritage and farmers get huge pride and satisfaction from farming sheep,” he said.

“Sheep farmers are managing one of our most precious resources – grassland – while also producing a fantastic and nutritious food from it.”

He added that grassland stored carbon and supported wildlife, and the sheep sector was at the heart of rural communities that the public benefited from when they came to the countryside.