Warmer Octobers boost potential for higher OSR yields

A field trial set up to investigate the link between warmers Octobers and higher crop yields have revealed an unexpected plus of climate change for farmers.

The experiment - the first of its kind - used heated field plots to test the responses of oilseed rape to warmer temperatures.

The crop, planted in autumn and harvested early the following summer, is particularly sensitive to temperature at certain times of the year.

Annual yields vary by up to 30 percent as a result, and it is known that warmer temperatures in October are correlated with higher yields. The reason for this trend was previously unclear.

The results of the study by the John Innes Centre reveal that the temperature in October is surprisingly important for the timing of flowering.

It highlights that warmer Octobers result in a delay to flowering the following spring.

Professor Steve Penfield an author of the study said: “Oilseed rape stops growing when they go through the floral transition at the end of October, and warmer temperatures at this time of year enable the plant to grow for longer, giving more potential for higher yields.”

The good news for growers of oilseed rape is that Met Office data shows cold Octobers are now much less frequent than they were in the past.

“By establishing the link between autumn temperatures and yield, our study highlights an example of climate change being potentially useful to farmers.

“Cold Octobers have a negative effect on yield if you are growing oilseed rape, and these are now rarer,” he said.

Temperature is critical for oilseed rape lifecycle because it determines at what point the plant goes through the transition from vegetative state to flowering, with delays in flowering being associated with higher yields.

This process called vernalisation is well understood in the lab as a requirement of a prolonged exposure to cold temperature.

But an increasing body of research suggests vernalisation might work differently under more variable conditions experienced by a plant in the field.

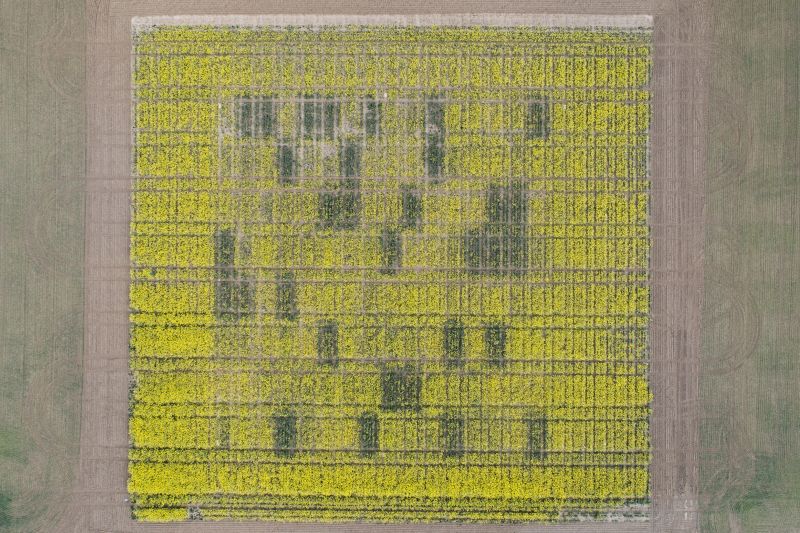

In this study the team used soil surface warming cables to raise the temperature of field plots by between 4 and 8 degrees Celsius, simulating warmer October temperatures. Two varieties of oilseed rape with differing vernalisation requirements were trialled.

Lab tests on dissected plants showed that warming in October conditions delayed floral transition by between 3 and 4 weeks for both varieties.

Genetic tests showed genes associated with vernalisation in cold conditions were also highly expressed in the warm conditions.

The study shows that vernalisation in oilseed rape takes place predominantly during October during which time the mean temperature is between 10-12 degrees Celsius.

The technology used in the study has been used before in natural grasslands to simulate winter warming but the trials conducted by the John Innes team are the first time it’s been used on a crop in the field.

“This study was only possible because were able to create the lab into a field to simulate how climate change is affecting UK agriculture,” Professor Penfield added.

“It’s important to be able to do this because yield is highly weather dependent in oilseed rape and it is very likely that climate change will have big consequences for the way we can use crops and the type of variety that we need to deploy.”